<em>In vitro</em> activity of <em>Lasioseius penicilliger</em> (<em>Arachnida</em>: <em>Mesostigmata</em>) against three nematode species: <em>Teladorsagia circumcincta</em>, <em>Meloidogyne</em> sp. and <em>Caenorhabditis elegans</em>

Main Article Content

Abstract

Veterinaria México OA

ISSN: 2448-6760

Cite this as:

- García-Ortiz N, Aguilar-Marcelino L, Mendoza-de-Gives P, López-Arellano ME, Bautista-Garfias CR, González-Garduño R. In vitro activity of Lasioseius penicilliger (Arachnida: Mesostigmata) against three nematode species: Teladorsagia circumcincta, Meloidogyne sp. and Caenorhabditis elegans. Veterinaria México OA. 2015;2(1). doi: 10.21753/vmoa.2.1.340.

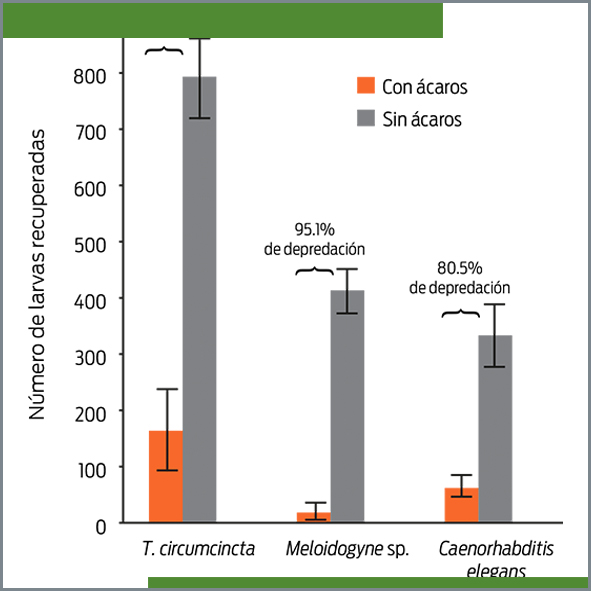

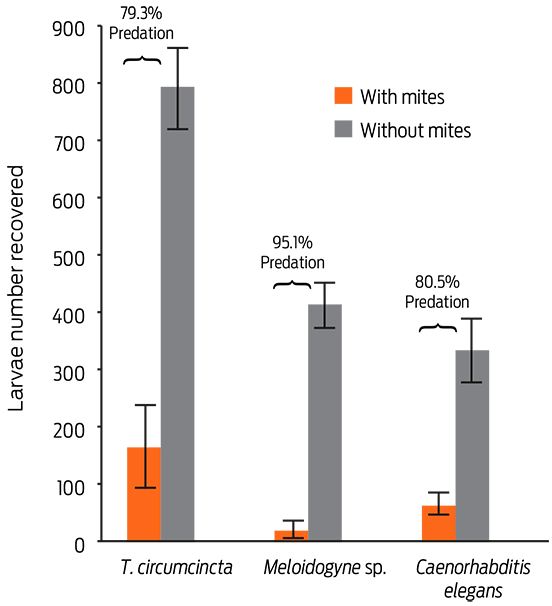

The aim of this study was to evaluate the predatory behavior in vitro of the mite Lasioseius penicilliger on 3 nematode species: Teladorsagia circumcincta (L3) (a sheep-parasitic nematode), Meloidogyne sp. (J2) (a plant-parasitic nematode), and on various developmental stages of Caenorhabditis elegans (a free-living nematode). The confrontation between mites and nematodes was individually assessed in 2% water agar placed in plastic Petri dishes (2 cm x 1 cm diameter). One thousand nematodes of a species and 5 mites were placed into each plate (10 replicates) and incubated for 5 days at room temperature (18-25ºC). L. penicilliger showed voracious feeding activity against the 3 assessed nematode species. The percentages of predatory activity recorded were 95.1, 80.5 and 79.3 against Meloidogyne sp., C. elegans, and T. circumcincta, respectively (P ≤ 0.05). These results suggest that L. penicilliger has important potential as a biological control agent of parasitic nematodes.

Article Details

References

1) Aguilar-Marcelino L, Quintero-Martínez MT, Mendoza de Gives PME, López-Arellano ME, Liébano-Hernández E, Torres-Hernández G, González-Camacho JM, Cid del Prado I. 2014. Evaluation of predation of the mite Lasioseius penicilliger (Arachnida: Mesostigmata) on Haemonchus contortus and bacteria-feeding nematodes. Journal of Helminthology, 88:20-23.

2) Back MA, Haydock PPJ, Jenkinson P. 2002. Disease complexes involving plant parasitic nematodes and soil borne pathogens. Plant Pathology, 51:683-697.

3) Bilgrami AL. 1994. Predatory behavior of a nematode feeding mite Tyrophagous putrescentiae (Sarcoptiformes: Acaridae). Fundamental and Applied Nematology, 17:293-297.

4) Bilgrami AL. 2008. Biological control potentials of predatory nematodes. In: A. Ciancio, KG Mukerji (editors) Integrated Management and Biocontrol of Vegetable and Grain Crops Nematodes, Springer.

5) Bjornlund L, Ronn R. 2008. “David and Goliath” of the soil food web-Flagellates that kill nematodes. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 40:2032-2039.

6) Carvalho S, Phillips CP, Teotónio H. 2014. Hermaphrodite life history and the maintenance of partial selfing in experimental populations of Caenorhabditis elegans. Evolutionary Biology, 14:117. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/14/117.

7) Chen YL, Xu CL, Xu XN, Xie H, Zhang BX, Qin HG, Zhou WQ, Li DS. 2013. Evaluation of predation abilities of Blattisociusdolichus (Acari: Blattisociidae) on a plant-parasitic nematode, Radopholus similis (Tilenchida: Pratylenchidae). Experimental Applied Acarology, 60:289-298.

8) Davies K, Spiegel Y (eds.) 2011. Biological control of plant-parasitic nematodes: building coherence between microbial ecology and molecular mechanisms. Springer.

9) Dutta TK, Stephen JP, Kerry BR, Gaur HS, Curtis RHC. 2011. Comparison of host recognition, invasion, development and reproduction of Meloidogyne graminicola and M. incognita on rice and tomato. Nematology, 13:509-520.

10) El-Banhawy EM, Osman HA, El-Sawaf BM, Afia SI. 1997. Interaction of soil predacious mites and citrus nematodes (parasitic and saprophytic), in citrus orchard under different regime of fertilizers. Effect on the population densities and citrus yield. Anzeiger für Schädlingskunde, Pflanzenschtuz, Umweltschutz, 70:20-23.

11) Fitzpatrick JL. 2013. Global food security: the impact of veterinary parasites and parasitologists. Veterinary Parasitology, 195:233-248.

12) Good B, Hanrahan JP, Theodorus de Waal D, Patten T, Kinsella A, Oliver LC. 2012. Anthelmintic-resistant nematodes in Irish commercial sheep flocks-the state of play. Irish Veterinary Journal, 65(1):21. DOI: 10.1186/2046-0481-65-21. http://www.irishvetjournal.org/content/65/1/21.

13) Gossner AG, Venturina VM, Shaw DJ, Pemberton JM, Hopkins J. 2012. Relationship between susceptibility of blackface sheep to Teladorsagia circumcincta infection and an inflammatory mucosa T cell response. Veterinary Research, 43:26 http://www.veterinaryresearch.org/content/43/1/26.

14) Gravato-Nobre MJ, Evans K. 1998. Plant and nematode surfaces: their structure and importance in host-parasite interactions. Nematologica, 44:103-124.

15) Hodda M, Cook DC. 2009. Economic impact unrestricted spread cyst trophic composition. Phytopathology, 99:1987-1393.

16) Hughes AMH. 1976. The mites of stored food and houses. Technical bulletin 9. London, England: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

17) Imbriani IY, Mankau R. 1983. Studies on Lasioseius scapulatus, a mesostigmatid mite predaceous on nematodes. Journal of Nematology, 15:523-528.

18) Indre D, Balint A, Hotea I, Sorescu D, Indre A, Darabus G. 2011. Trichostongyles species and other gastrointestinal nematodes identified in sheep from Timis County. Bulletin UASVM, Veterinary Medicine, 68:171-178. http://journals.usamvcluj.ro/index.php/veterinary/article/viewFile/6897/6159.

19) Kaplan RM. 2004. Drug resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance: a status report. Trends in Parasitology, 20:477-481.

20) Luc M, Sikora RA, Bridge J. 2005. Plant parasitic nematodes in subtropical and tropical agriculture. 2nd ed. London, UK: CAB International. pp. 1-10.

21) Mendoza de Gives P, Torres Acosta JFJ. 2012. Biotechnological use of fungi in the control of ruminant parasitic nematodes. En: Paz Silva A, Sol M (eds.) Fungi: Types Environmental Impact and Role in Disease. : Nova Science Publisher, Inc. pp. 389-408.

22) Raleigh MG, Brandon MR, Meeusen E. 1996. Stage-specific expression of surface molecules by the larval stages of Haemonchus contortus. Parasite Immunology, 18:125-132.

23) Roeber F, Jex AR, Gasser RB. 2013. Impact of gastrointestinal parasitic nematodes of sheep, and the role of advanced molecular tools for exploring epidemiology and drug resistance-an Australian perspective. Parasites & Vectors, 6:153. DOI: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-153 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/6/1/153.

24) Safdar AA, McKenry MV. 2012. Incidence and population density of plant-parasite nematodes infecting vegetable crops and associated yield losses in Punjab Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 44:327-333.

25) SAS Institute. 1998. Statistical software Ver. 6.03. Cary, North Carolina, USA.

26) Sayre RM, Walter DE. 1991. Factors affecting the efficacy on natural enemies of nematodes. Annual Review Phytopathology, 29:149-166.

27) Sikora RA, Fernandez E. 2005. Nematode parasites of vegetables. En: Luc M, Sikora RA, Bridge J (eds.) Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture, 2nd ed. Wallingford, UK: CAB International. pp. 319-392.

28) Timper P. 2011. Utilization of biological control for managing plant-parasitic nematode. En: Biological Control of Plant-Parasitic Nematodes. Hokkanan HMT (ed.) Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York. pp. 259-260.

29) Thienpont D, Rochette F, Vanparijs OFJ. 1986. Diagnosing helminthiasis by coprological examination. 2nd ed. Beerse, Belgium: Janssen Research Foundation. pp. 35-36.

30) Torres-Acosta JFJ, Molento M, Mendoza-de-Gives P. 2012a. Research and implementation of novel approaches for the control of nematode parasites in Latin America and the Caribbean: is there sufficient incentive for a greater extension effort? Veterinary Parasitology, 186:132-42.

31) Torres-Acosta JFJ, Mendoza-de-Gives P, Aguilar-Caballero AJ, Cuéllar-Ordaz JA. 2012b. Anthelmintic resistance in sheep farms: update of the situation in the American continent. Veterinary Parasitology, 189:89-96.

32) Van der Putten WH, Cook R, Costa S, Davies KG, Fargette M, et al. 2006. Nematode interactions in nature: models for sustainable control of nematode pests of crop plants? Advances in Agronomy, 89:227-260.

33) Van Wyk JA, Mayhew E. 2013. Morphological identification of parasitic nematode infective larvae of small ruminants and cattle: a practical lab guide. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research, 80(1). DOI: 10.4102/ojvr.v80i1.539 http://www.ojvr.org/index.php/ojvr/article/view/539.

34) Walter DE, Kaplan DT, Davis EL. 1993. Colonization of greenhouse nematode cultures by nemathophagous mites and fungi. Supplement to Journal of Nematology, 25(4S): 789-794.

35) Walter DE, Lindquist EE. 1997. Australian species of Lasioseius (Acari: Mesostigmata: Ascidae): the porulosus-group and other species from rainforest canopies. Invertebrate taxonomy, 11(4):525-547.

License

Veterinaria México OA by Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia - Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence.

Based on a work at http://www.revistas.unam.mx

- All articles in Veterinaria México OA re published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC-BY 4.0). With this license, authors retain copyright but allow any user to share, copy, distribute, transmit, adapt and make commercial use of the work, without needing to provide additional permission as long as appropriate attribution is made to the original author or source.

- By using this license, all Veterinaria México OAarticles meet or exceed all funder and institutional requirements for being considered Open Access.

- Authors cannot use copyrighted material within their article unless that material has also been made available under a similarly liberal license.